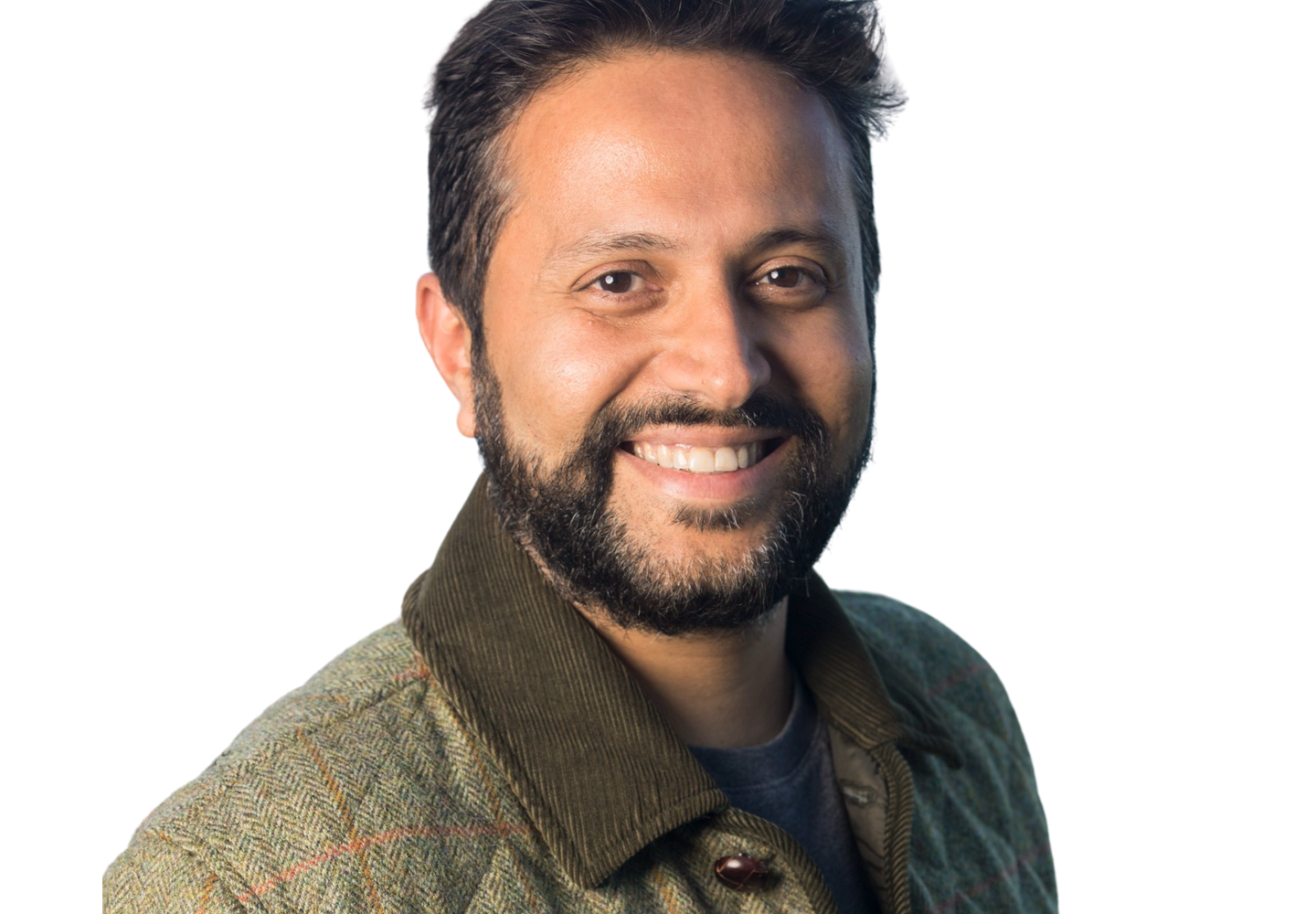

What problem inspired the creation of Fauna, and why were you the right person to tackle that?

The founders of Fauna were two deeply technical data infrastructure engineers who had come out of Twitter. They experienced the challenge of scaling Twitter’s infrastructure firsthand. They happened to be starting out on a relational database and tried all the NoSQL alternatives that had come up in the mid-2000s. They thought teams needed a better way to scale their applications and infrastructure on the internet. There were good attributes from both MySQL and the NoSQL databases they used, and they wanted to combine them to make it much easier for people to build and scale modern web applications.

And then why me? I joined in 2020 after Madrona invested in the company. The core team had developed a great architecture and attracted a lot of initial developer interest in their service. And it was time to start turning this into a business.

I had spent the prior decade building another infrastructure software company called Okta, where I was the chief product officer. There were a lot of similarities between the two. So, I joined to help evolve the product to be enterprise-grade and start attracting enterprise customers.

What is it like to work with Madrona?

Madrona understands early-stage businesses and the requisite ups and downs associated with them. And, in our case, they also understand some of the unique challenges associated with building a core infrastructure business like a database business. It takes a lot of capital and time to get it off the ground, so understanding that is important. I get the feeling that Madrona is in it with us. It’s been challenging, especially given the financing environment the last couple of years. Madrona has done a lot to help us continue to attract new investors and to help across recruiting, sales, marketing, and other aspects of the business.

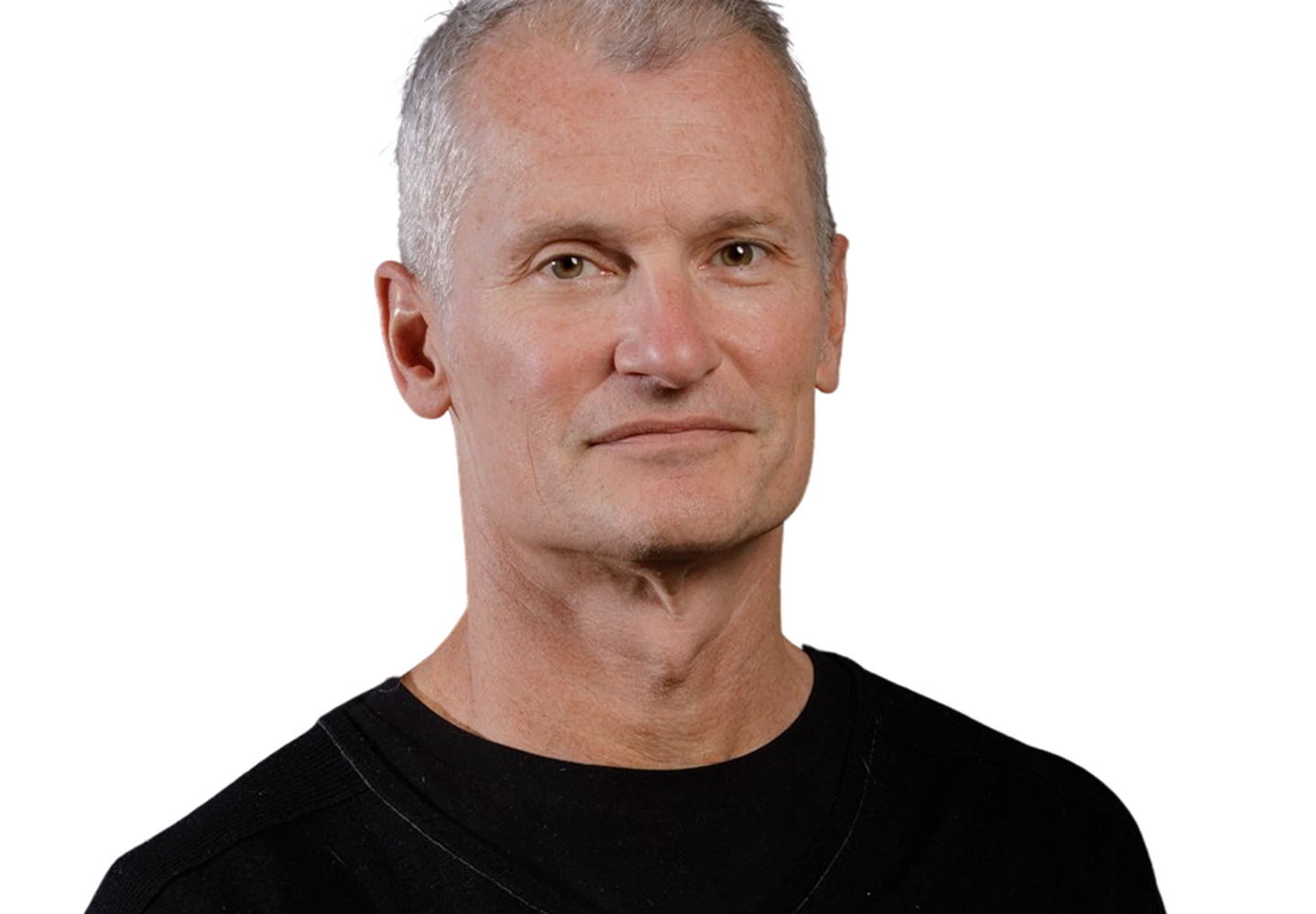

Soma, in particular as our board member, has domain experience in infrastructure and developers, and he has been a trusted adviser and sounding board when it comes to navigating all aspects of running a company: the board dynamics, organizational change you have to drive as a leader, and the things a CEO has to think about more broadly in the company. Soma has always been a good voice of reason that encourages you to focus on the team, the business, and the customers and not to get distracted by all the other hype that’s going on in the industry or crazy things you might be hearing from other investors or competitors.

Madrona understands early-stage businesses and the requisite ups and downs associated with them.

Tell us about a Madrona Moment.

I’ve been a part of several early-stage startups and worked with many different investors, but this is my first time as CEO. Fauna has benefited from support and introductions across recruiting, sales, strategic partnerships, and investors from many people beyond Soma at Madrona, including Matt McIlwain, Tim Porter, Ted Kummert, Katie Chupka, Shannon Anderson, and Joanna Black.

One area in particular that has been unique relative to the support I have experienced from investors in the past has been working with Joanna Black, Madrona’s general counsel. As an early-stage company, you don’t have the luxury of a full-time, experienced general counsel. So that usually means tapping into outside counsel, which do provide excellent guidance but can also be very expensive. Joanna has provided great advice and, in some cases, rolled up her sleeves alongside us to navigate a variety of funding and business situations. She has even provided references to specialized outside counsel we could tap into, all of which helped us maximize our return on our legal spend and resulted in better outcomes for the company.

What have you learned about yourself during this process?

As a first-time CEO, there have been two big learnings for me. First, I learned I like the breadth of the role — the ability to think left to right across all aspects of building a company, whether it’s team or product or office space or how you ramp customers. It’s been interesting and fulfilling and something I find appealing. At the same time, having worked for a lot of CEOs before, I learned that I didn’t appreciate the amount of time the CEO has to spend on critical company-building activities that are not focused solely on customers and product, which was my focus as a product leader.

To build a healthy company, CEOs have so many other things, whether it’s thinking about the culture you want to instantiate, how to measure and reward performance across the organization, dealing with investors and fundraising, what your hybrid work strategy is going to be, and surviving the barrage of inbound emails from every vendor out there who wants part of your time. I underappreciated the breadth of activities that you have to take on. It’s given me an appreciation for times when I’ve thought, “Why isn’t the CEO focused on this one thing that I think is so important.”

What is the most important lesson you have learned during your startup journey?

One of the most important jobs of the CEO is to always have enough money in the bank. But beyond that, making sure you have the right talent at the right time is also critical. I’ve always been a stickler on talent, and I have a very high bar for recruiting when building out the team. I think anybody who steps into a CEO role or builds a startup has big aspirations for why they’re investing their time to do this and how they want to see that company grow.

When you’re doing startup recruiting, you’re doing a lot of evangelizing about the opportunity, how big it’s going to be, and what’s going to happen. But one of the most important lessons I learned was to balance that with ensuring you are finding people who are good for the job that needs to be done now and for the next couple of quarters or the next year. The skill sets you need at five or 10 employees are very different than when you’re at 100 or 500. Ideally, that person in the particular role will scale as the company scales, and you’ll do your best to make that happen, but you don’t want to end up on the other side, which is over-optimizing for the person who you think is going to be great once the company scales, but maybe isn’t well suited or excited about the day to day of a very early stage company. You have to strike that balance. And it’s a fine line to walk.