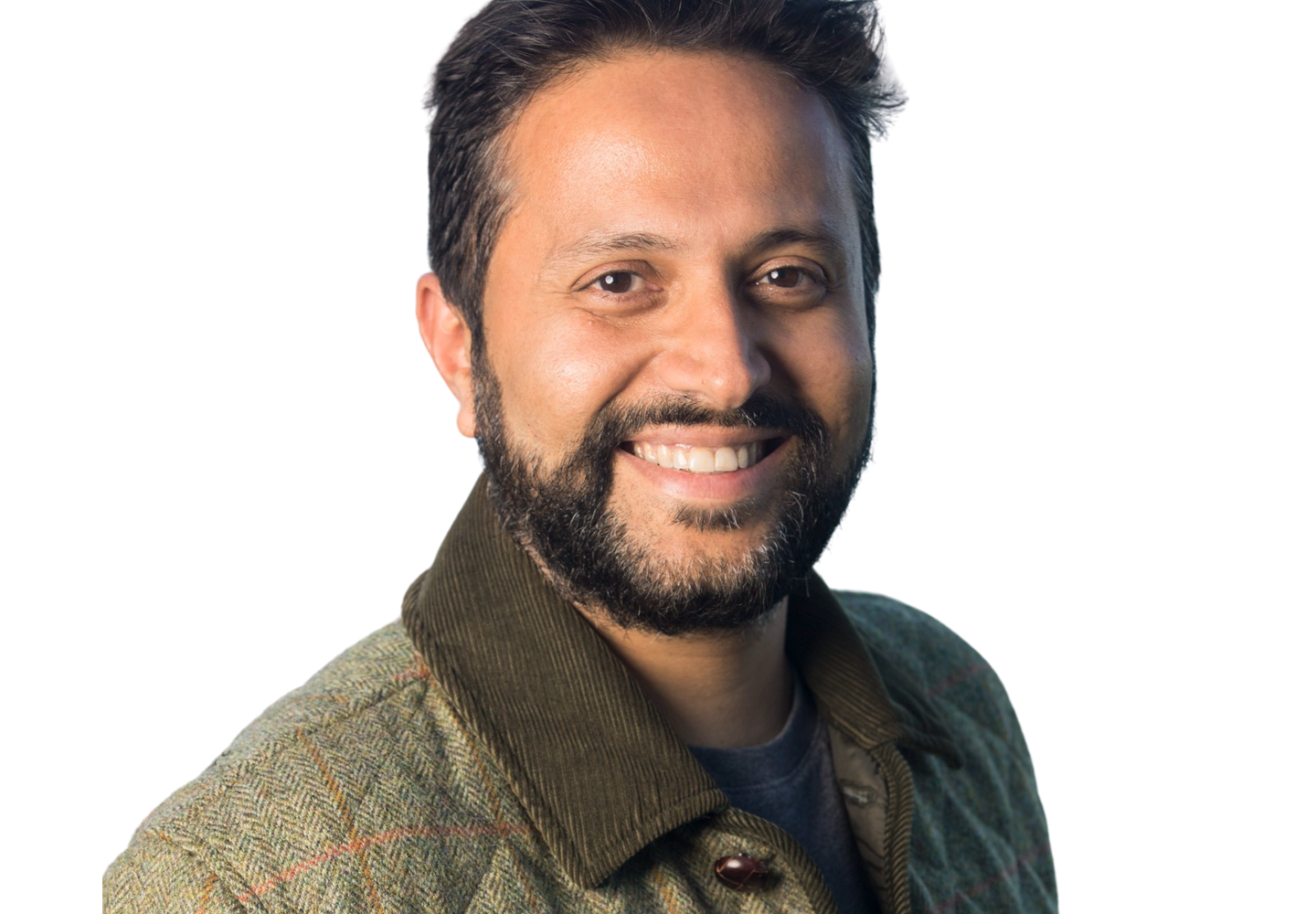

What problem inspired the creation of Impinj, and why were you the right person to tackle that?

Today, Impinj is the leader and pioneer in RAIN RFID, a technology we and many others use to connect everyday items to the internet. This industry enabled the connectivity of roughly 45 billion items last year and is still growing. But when we started the company, we didn’t have that in mind at all.

My background is in wireless, and we started Impinj in 2000 with a technology for very low-power analog circuits. We were initially looking at applying our technology to this big new thing called 3G wireless. But then, the dot-com bubble burst, the bottom fell out of the market, and we were left wondering, “What are we going to do?” We ended up latching onto what was then just known as RFID. RFID is a zero-power radio that absorbs its operating energy from radio waves and uses that energy to communicate back and forth. You can put a chip with a zero-power radio on anything because you don’t need a battery. So, we developed a new approach to RFID that would enable extending the internet to everyday items.

Nine months after we decided to jump into the space, Walmart announced they were going to be using RFID to track all pallets and cases. So, we all high-fived, thinking how lucky we were to choose the right thing and that we were months away from IPO. But there were some hurdles to overcome: there were no radio standards for RFID at the time, no spectrum was allocated anywhere in the world that we could use, and neither we nor anyone else had any products.

It was a crazy, exciting, and difficult time because we endeavored to do fundamentally hard things. There was also a lot of competition because of the Walmart announcement, but we persevered. About two years after we founded the company, we settled into the space we’re in now.

We’re the sole company in our field that successfully went public and is still the leader.

We could never have gotten to where we are without Madrona. … I always had the fundamental belief that they would roll up their sleeves with us and say, “Okay, let’s get past this challenge.”

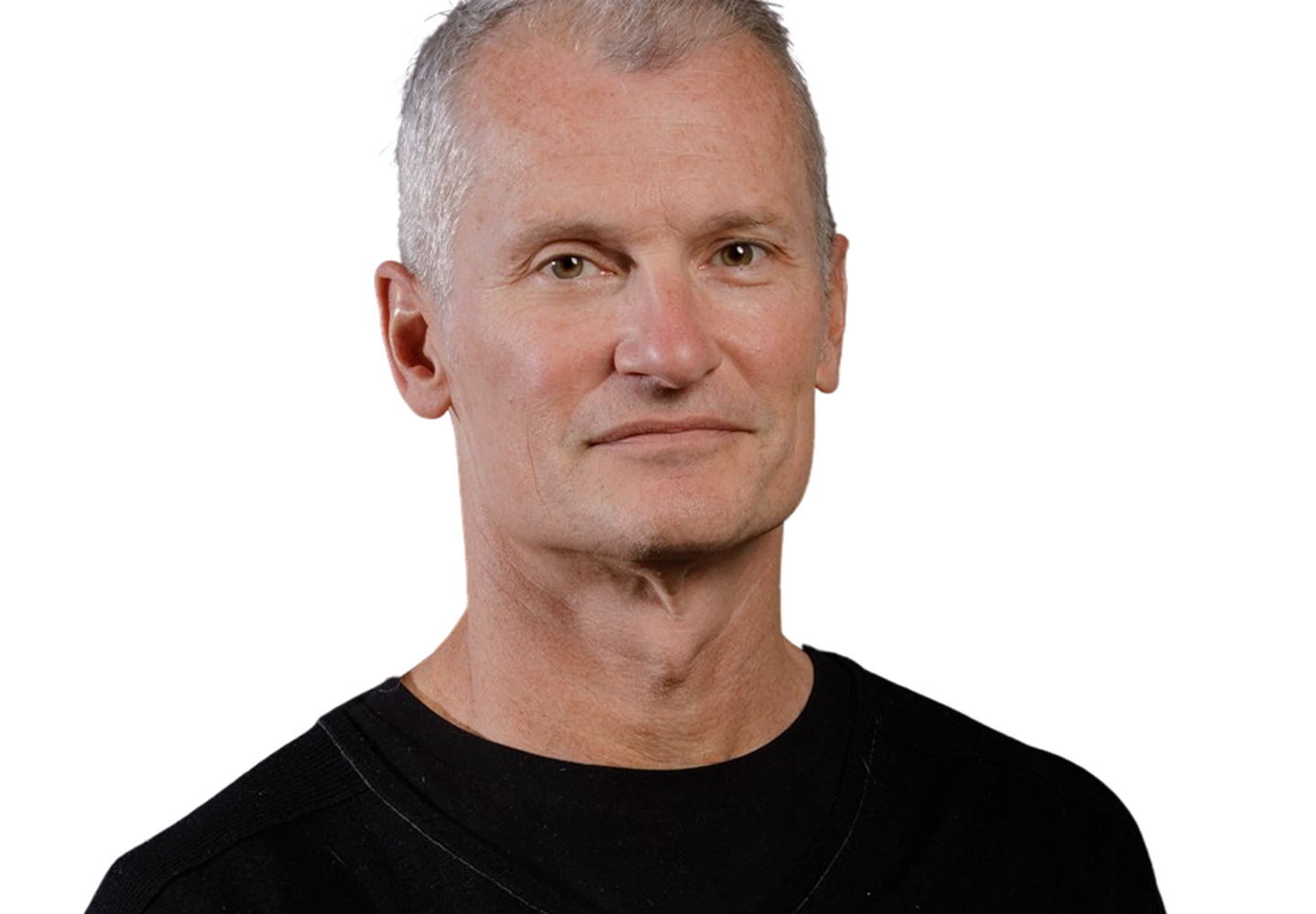

What is it like to work with Madrona?

In the beginning, we worked with Madrona and Arch Venture Partners. We had interest from a lot of other venture firms, but Madrona stood out as a firm that would stand behind their companies for a long time to help them succeed. We had Tom Alberg on our board for 20 years. He was incredibly supportive and helpful to us as a company, but there were a lot of other Madrona people who helped us along the way as well.

One of the things I tell people about Madrona is that if Impinj had been funded by a venture capital firm whose mantra is “fail fast,” we would never have succeeded. That approach is designed for quick-hit results. But Impinj is not a quick-hit result. We’re doing a fundamentally transformative technology that’s, quite frankly, bigger than anything any single company, in my view, has done before – connecting every item on the planet to the internet. I mean, how big is that? You can’t do that quickly. The “fail fast” venture capitalists would have found a way to sell off the assets, and we would have failed. Madrona stuck with us. It took us 16 years to get to IPO. We’re now 24 years in, and it was at about our 20th year when things took off for us as a company and you could see the vision being realized.

Madrona was willing to stay with us, to see the vision, to give us time to realize the vision and to be part of the company for 16 years until we went public. Even after our IPO, Madrona continued to be part of the company, letting us come back to the office and seek advice from Tim, Tom, and others. I believe that that level of support is unique in the venture capital industry. Said another way, we could never have gotten to where we are without Madrona.

Tell us about a Madrona Moment.

I think we had multiple Madrona moments. When we were stuck on something, we would go to the Madrona offices for a day or two and hole ourselves up in a conference room to work through the challenges we faced. Tom, Tim, or somebody else would come in and listen to what we were doing and give us advice. We knew we could come to the Madrona team confidently with a problem and expect that the Madrona team would help us solve the challenges instead of saying, “Oh my gosh, this is a disaster. We’ve got to run for the hills.” I always had the fundamental belief that they would roll up their sleeves with us and say, “Okay, let’s get past this challenge.”

What have you learned about yourself during this process?

I never thought I’d lead a company. I have always been a fairly independent person, so if you had asked me 25 years ago whether I would lead a company, I would have said, “Really, me? No. It’s not going to happen.”

Although I love technology, helping people out, and working within a team to move things forward, I am not the kind of person who feels like I have to grab things and help get them done. I’m happier working on something of my own, trusting other people to work on the things they need to work on, and being there in more of a professor role, lending support when it’s needed.

I’m surprised that, though I never sought to lead a company, I found a positive way to do it. I am also surprised someone can build a company while maintaining a core focus on providing a vision and culture that allows employees to feel empowered and be the best they can possibly be.

My No. 1 job as a CEO is to give every person in the company the opportunity to be wildly successful. I truly feel that if every person in the company is wildly successful, the company can’t help but be wildly successful. I tell all the employees that their job is to help every one of our customers be wildly successful because if our customers are wildly successful, that is meaningful for everyone: employees, customers, and the company.

I’ve heard that kind of mindset is not very common, but it should be. If you hire good people, give them the opportunity to succeed, and then unleash them, they can do more than any one person, any one executive team, or any one leadership team could ever accomplish.

What is the most important lesson you have learned during your startup journey?

The more confident you are that you’re right about something, the less likely it is you are right about something. You should always have a very healthy amount of self-doubt. You should share your ideas broadly and let other people challenge them because, in that attempt to share your ideas and explain them and get feedback from others, you’ll learn an immense amount. People are very willing to critique your ideas, and you should take that opportunity because through that critique, you will get to a good answer.

Anybody can have a good idea. Walmart first adopted RFID because a laboratory technician had an idea to use radio chips for inventory visibility that had the potential to extend broadly to supply chain traceability. That lab technician — and this is a unique thing about how Walmart operates — set up a meeting with the CTO and said, “I have an idea.” It wasn’t top-down; it was completely bottom-up from somebody in the lab who had a good idea. The most successful way to build a strong company culture is to allow everybody to come forward with their ideas and leverage the power of the team.

Finally, as the CEO, I’m going to make plenty of mistakes along the way, but if I allow everybody to be empowered and successful, people will come forward and tell me, “Chris, you’re blowing it,” — which they do. And I’m happy to hear that because it allows me to course-correct early on.