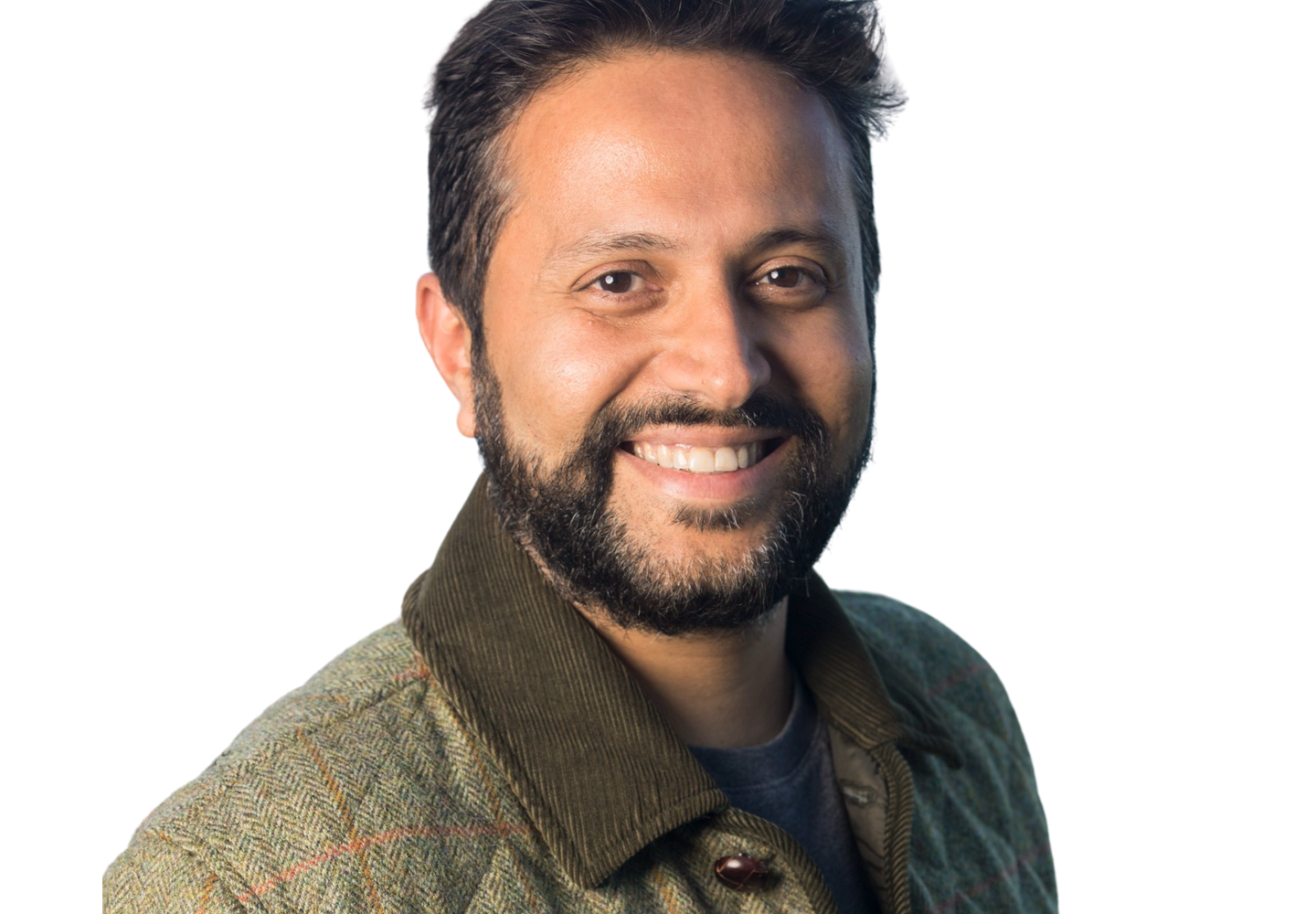

What problem inspired the creation of Stacklok, and why were you the right person to tackle that?

The origins of Stacklok can be traced back to my lived experiences with open-source software, as a co-creator of the Kubernetes project. I’ve seen open source as an incredible source of innovation for the technology industry, and I’ve had the privilege of working in healthy, vibrant open-source communities and seeing how much power and energy they can bring to the technology space. One observation and point of fascination that turned into a point of consternation, and then, eventually, a point of profound concern was the idea that while open source represents roughly 90 percent of the shipped software out there, the people repackaging and redistributing open source had very little awareness of where it came from. They didn’t know whether it was built responsibly and sustainably or what choices went into constructing the technology that underpins almost everything in modern society. This represents something that I feel is an incredible challenge for humanity, particularly as we see a sea change in terms of how hostile actors are operating, like the XZ Utils incident, for example. The level of sophistication is higher and the approaches hostile actors take are changing. I felt like something needed to be done.

To solve a community-centric problem, I believe you need a community-centric solution. My co-founder and I both have roots in open-source communities and have been very successful in advocating for community-centric development. At the end of the day, the solution requires platform sensibilities. My background is in the construction of teams that produce platform-based outcomes like Kubernetes, Google Kubernetes Engine, Google Compute Engine, and all of the other things that I’ve worked on in my career.

Stacklok builds products that help developers securely develop and deploy software. I believe our community-centric, developer-friendly, platform-aligned approach will enable us to be uniquely successful in this space and create unique value in the world.

Making that kind of fateful connection and sponsoring [Shanis] into our organization changed the shape of our company.

What is it like to work with Madrona?

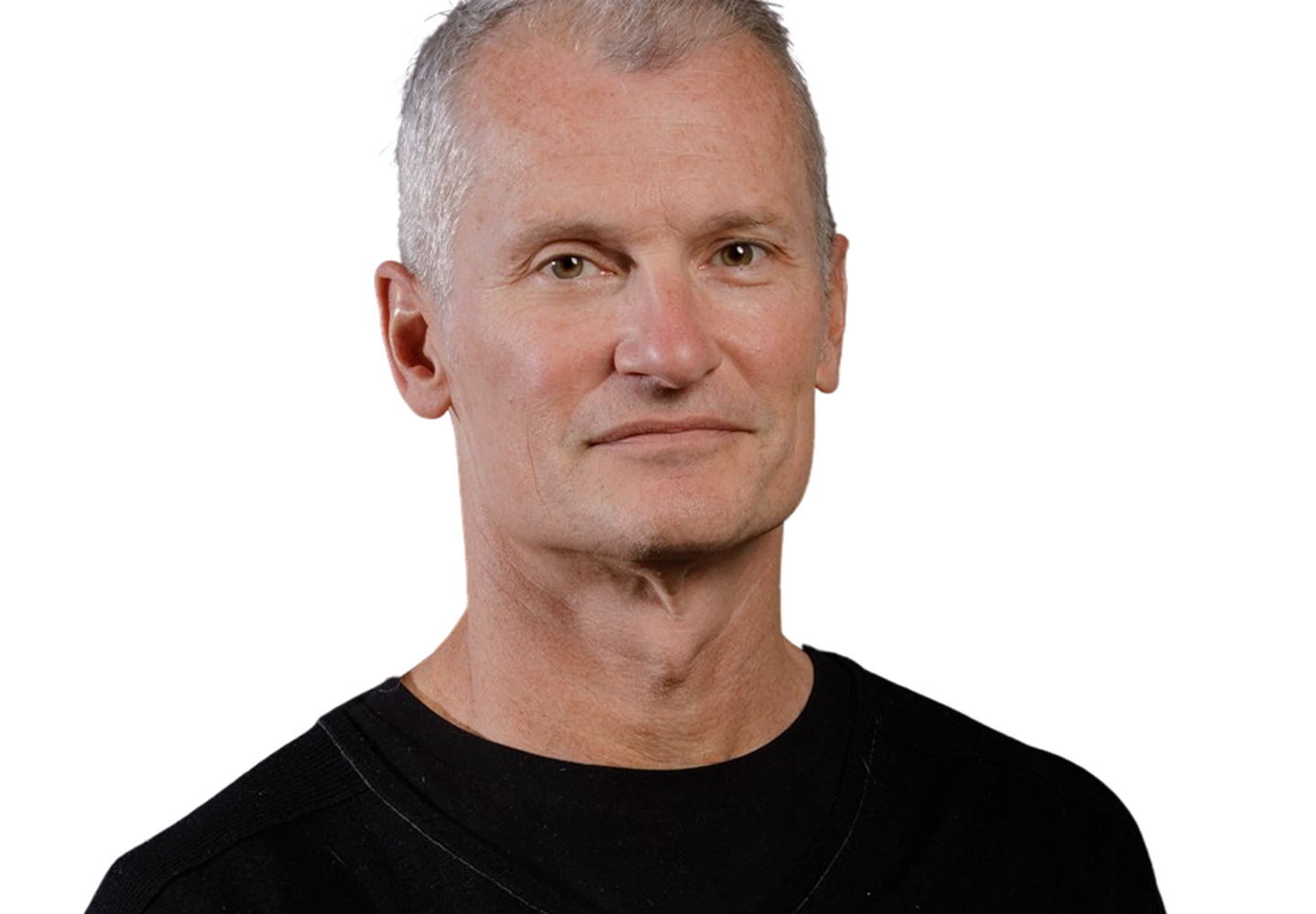

As someone who is not just a Madrona founder but a repeat Madrona founder, it tends to suggest I like working with Madrona. There are two things that are very important. The first is that the quality of the people matters. When you’re a startup founder, you are going to be on this fantastically long journey. It’s notoriously not an easy job, so you want to surround yourself with people who are going to support you, challenge you, and drive your success over time. That means the quality and the pedigree of the individual sitting on your board — and your relationship with that person — is critical to your success. For me, that was Tim Porter. I’d done my homework, and I considered him to be a class act when building Heptio. As I looked at who I wanted to work with again for Stacklok, he came to the front.

The second thing is that there is a lot of work associated with building a startup, and I’d seen Madrona as a company that actually puts in the labor—the intellectual, emotional, and physical labor. Whether introducing us to prospective clients or high-quality talent or supporting us as we tried to figure out key operational considerations, Madrona has always been extraordinarily helpful and has felt like a natural part of the journey.

Those two things, the people and putting in the work, really brought me back to Madrona when I was starting my second company.

Tell us about a Madrona Moment.

One of the Madrona moments for me was pretty early on. We had just launched Heptio and were mooching off Madrona, living in the Madrona offices, eating the Madrona snacks, drinking the Madrona sodas, and generally living the Madrona life. We were a relatively new company, and I was a relatively new founder. I didn’t have a lot of experience in the ecosystem, and we really needed someone who could help shape the operations of the organization. Tim said, “This is what you need, and I’m going to introduce you to a few people who I think will be able to change the course of your existence.” He introduced me to Shanis Windland, who eventually became the VP of finance/CFO of Heptio. She was a critical facet of building Heptio’s culture and has joined me in my second attempt now with Stacklok as our COO.

It is that access to industry-shaping talent, someone who Tim had personally seen operate in a variety of different contexts, had taken the time to build the relationship with, and was able to, in the moment, understand how important that person’s DNA, character, and skills were going to be to us and our journey as an organization. Making that kind of fateful connection and sponsoring her into our organization changed the shape of our company. Having access to that kind of talent was incredibly transformational for us.

What have you learned about yourself during this process?

What surprised me the most was that I really enjoyed selling things. I had no idea that it was something I would find interesting and captivating. But the athleticism associated with the sales process — working hand in glove with a capable sales leader to drive business success — I certainly didn’t expect to enjoy it as much as I did. I knew there was a dark art to go to market, but I didn’t know what it looked like. I enjoyed that side of building the business, which I would never have imagined about myself.

What is the most important lesson you have learned during your startup journey?

If I could go back and do it again, I wish I would have recognized that people in my position now — those who have built companies, exited companies, and built up a base of experience — delight in helping early founders. I wish I had known I could actually pick up the phone and authentically call someone like me now and get answers to questions. When you’re a startup founder, particularly a first-time founder, you will encounter many situations for the first time. You don’t have the instincts, awareness, and knowledge to fall back on. You spend a lot of energy trying to derive things from first principles — decisions that are, in hindsight, obvious.

If I had called Tim, my VC partner, he would certainly have answered these things, but at the same time, you want to stand on your own a little bit. You don’t want to be running to your board every time you encounter something you don’t understand. I wish I had recognized there is a strong and vibrant community of other founders out there who are more than happy to step forward and support you and answer questions — and who enjoy doing it. They want to pay it forward to the next version of themselves.