In this episode of Founded and Funded, we stray a little from our typical format to answer some questions that often come up in discussions between founders and our investors. Madrona Managing Director Matt McIlwain talks with one of our Limited Partners — a partner that is not a day-to-day investor — Top Tier Capital Partners Founder and Managing Director David York. They explore different kinds of funding mechanisms and how David is “selfishly optimistic” about the current market environment. And they talk about the history between the two firms – more specifically, why this San Francisco-based firm decided to bet on Seattle and Madrona all those years ago!

This transcript was automatically generated and edited for clarity.

Matt: This is Matt McIlwain. I’m a Managing Director at the Madrona Venture Group, and I’m just delighted to have a longtime friend and special guest here today — David York. He’s somebody that I’ve known now for over 20 years, and his is a really interesting journey going back to what was once called Paul Capital and had a focus on what’s called the secondary market, and how David under his leadership and with this amazing team, has really transformed it into a much bigger set of platforms. David, can you take us back to Paul Capital and how that evolved into Top Tier.

David: Sure, our pedigree actually goes back to the 1980s with the Hillman family, which is also a co-investor with us in the Madrona funds. My co-founder Phil Paul from Paul Capital used to run that portfolio in the 1980s. And at that time, the only investors in venture capital firms, or at least a lot of them, were either corporations like AT&T, which was one of the largest programs at the time, and/or families — endowments for the most part had not started to invest in venture capital and hadn’t really thought of that model. So, our legacy in this industry goes back almost 40 something years. I had the privilege in the ’90s of running a trading desk for a venture capital investment bank in San Francisco called Hambrecht & Quist, and one of my clients was Paul Capital. They, as you’ve mentioned earlier, were focused on secondaries for most of the ’90s. But at the end of that decade, it attracted capital to invest in funds on a primary basis.

Matt: Maybe David, when you say primary and secondary and then for now let’s constrain it to funds and then we can go to direct companies. Maybe we’re just going to break all those down.

David: So, when a fund is getting formed, it’s typically a blind pool. And the investment into that blind pool is usually by an accredited investor or an institution, and they usually are really trusting the folks, like the partners at Madrona, to manage that money going forward over a period of time. That initial investment into that fund is called a primary investment in our industry. You can use that same terminology to be an initial investment in a private company as well, but for limited partners, primaries are buying funds for the first time without any assets in them.

If you look at the contracts that are used to create those funds, things like defaulting on your commitment are very onerous and can be quite penal as it relates to your investment — you can forfeit your assets, you can forfeit a lot of things. And so, it’s not common that investors default on their commitments if they want to get out of, say, a venture fund. But one of the ways they can remove themselves from a venture fund, if they want to invest that money someplace else, is to sell them. And that sale transaction happens in what we call today, the secondary market. Think of that as sort of a tertiary market like used cars. Well, this is used private equity. And that was one of the early inventions that Phil Paul created when he started Paul Capital — that firm was started under the guise of a very large secondary transaction — one of the very early secondary transactions ever done in our industry.

Secondaries today now make up about 5 to 10% of the volume in the private equity industry. It’s a way to invest in private assets, typically companies, in a manager that you might know and trust, later in their life. And so, there’s a lot of visibility on what’s in those portfolios, as well as if you have some insight, you have some visibility on how those companies might do in a way that you can actually generate pretty attractive returns. You cannot generate for the most part the same type of return as if you invested in that fund at the very beginning but depending on the markets and the pricing you can acquire the secondary interest in, once it’s further along, you can generate returns that look pretty comparable.

Matt: So here is this organization, Paul Capital. They develop an expertise for buying these secondary stakes in venture capital funds. So, this is not yet at the secondary stake in an individual company level let’s pick up the story in the kind of the early 2000s.

David: Phil and I spent most of the early 2000s building what’s today our core fund to funds business. It’s 80-90% of what we do and did then — invest in funds on a primary basis, so when they got started. From time to time, we get an opportunity to buy a secondary in one of our managers as we went along, and so we would do that. With the global financial crisis, we started to see more and more secondary volume as an active fund investor in our managers, primarily driven by institutions that were essentially desperate to generate liquidity because of what had happened in the global financial crisis. And that motivated us to look at what was for sale versus what people were worried about and we realized that the worry was much higher than what they were selling, and the quality of what they were selling was quite good. So, we started aggressively buying fund interest in our managers at really very attractive prices.

I mean, think 30, 40, 50% of a discount to what the current NAV was, and that motivated us to really start to build a capital base there. So today about a third of our investment activity is focused on buying these secondaries. About 20% of what we do is then invest with our managers in the later stages of their developing portfolio companies. And usually, that’s in the B to C round, and that’s been a very lucrative investment activity for us as well. Today, we own indirectly and directly about 12,000 private companies. And we also have invested between our secondary purchases and our primary investments in about 500 different venture funds across about a 100+ general partners or managers. And that gives us a great lens on the industry, and that asset base generates quite a bit of interesting deal flow.

Matt: A lot of our audience are entrepreneurs, and what’s interesting from their perspective here is that here you are a great long-time investor — one of our limited partners — buying primary into Madrona. But then you can see through to the performance of our companies and then sometimes be a co-investor with us and a direct investor in them. And I know that you’ve done that both in terms of buying direct primary investments and in some cases, direct secondary, investments. In fact, I think your colleague Garth Timoll and you were champions of Smartsheet relatively early on. And that I think turned out to be quite a successful investment for all of us, of course, but from our perspective, it was great to have our trusted partners that were also interested in investing in our companies. And it’s a nice resource for those companies as well.

David: And we think that’s a perfect relationship with our managers. We want to be a source of capital that, thankfully, we think of as being a good partner. So, we want to help you build companies with our primary investments in your funds and then we want to help you with liquidity if you have an investor that can’t follow on, or somebody’s getting a divorce or an institution gets a new CIO, and they change their strategy, then we’ve enjoyed and had an opportunity to take advantage of those situations by buying funds from your limited partners. And then, you know, we do a handful of deals a year, so we’re not that active from the standpoint of co-investments, and we’re pretty picky, but we’ve enjoyed a great relationship with Madrona around some of the co-investments we’ve done from Qumulo to Smartsheet to Remitly and some others. One of the other things we’ve been able to do in the form of being a good partner is help some of those companies provide liquidity to their employees through tenders, which are actually direct secondaries in those companies. We look at those as a mechanism to provide more ownership to our investors in our programs to that good company. And we think it’s additive and based on the way capital markets are structured today — these companies are staying private longer — and so it gives CEOs and entrepreneurs the opportunity to help their employees get liquidity along the journey of the startup in a way that I think is constructive for everybody.

Matt: So now we’re onto secondaries directly in companies and buying shares, from an employee in theory, you could buy it from a former employee or one of the venture investors, maybe an angel investor. This is an area that I think we both agree the mindset in the venture community has changed quite a bit in the last 15-20 years. Can you maybe take us back to kind of the early 2000s mindset and how that’s changed in terms of secondary sales, especially for current employees at companies?

David: Sure. First of all, if you go back to the late ’90s, the average pre-money for an IPO was roughly $300 to $400 million — I mean, if you look at Microsoft and Amazon in particular, those that’s right in the range of where those companies were before they went public. Today that’s the average value of a Series C or a series D round, depending on how fast the business is growing and how much money they’re trying to raise. And so, the time pendulum of liquidity in the startup sort of model was you got paid enough to want to work there, but you really made your upside with your equity, and you got that liquidity from the companies going public earlier, and that’s kind of gone away. And it’s taken the investor community, meaning general partners and the limited partners, like you said, the last 15 years to get comfortable with the notion that those mechanisms are not going to change much as it relates to employee structure and whatnot. And so, it’s up to the private market investor to try and help with that. And we’ve all gotten much more comfortable in owning common. It used to be that we had to own the preferred to make ourselves feel comfortable, but as companies get big enough, which is usually where they’re typically doing these tenders, the preferred structures really are not necessary because the companies are moving well beyond that in a way that common is actually the same security in some ways.

And so that’s part of the reason we’re so comfortable with tenders is that it gives us more ownership. It gives us a better blended exposure. A lot of times the companies that we’ve done tenders with, if we’ve invested in on a direct basis or we’ll come back and do a direct round a little bit later on, and what we’re looking for is exposure to great companies that we see in our managers’ portfolios and trying to be a good partner along the way. We did one for an ad tech business down here in San Jose that they never raised any money beyond the seed round. The management team wanted liquidity, so they could kind of spend another three years doing their thing. And then ultimately the employee base wanted the same thing. And so, we did a couple of deals with them. Ultimately that company got acquired by Blackstone, and so we all did very well by it, but there was no real liquidity in the marketplace unless you did that for the employees and the management team.

Matt: You know, my mind got changed in this area maybe a decade or so ago in that you’re concerned that if people were selling, especially founders and employees, were selling their shares. They were going to be a little less aligned with the company. But I think they became more aligned with the venture investors because they were able to sell some and that could give a little bit of a release valve.

David: Yeah, Risk office as we call it, so that they can lean in even further.

Matt: And be less tempted if, you know, whether it’s a strategic or a finance — a Blackstone or somebody comes along and is trying to buy you, you can say we’re going to kind of play for the longer term, the bigger outcome. And I think that that does align with, with the venture investors. I mean, you must look through a lot of venture funds. And I’d be willing to guess that 90% of those venture funds end up having two, three, or at most four of the companies that are the ones that really move the needle in terms of the returns on those funds.

David: Yeah, those probabilities haven’t changed. No matter what decade we’re in. What’s changed in the venture capital fund investment universe today is that the dollar losses that a portfolio generates early on have really shrunk. And the reason for that is it just takes so much less capital to start a company. The number of companies that fail in a portfolio hasn’t really changed and it varies. But it over time ends up being somewhere between 20 and 50%. Of the ones that survive, half of those usually return the fund. And then the other half are where the drivers are. And just depending on how many companies you have in your portfolio in general, but that usually is in the neighborhood of two to three on the low end and maybe five or six on the high end. Every once in a while, you get a fund that has outliers in all those places, and they create really remarkable returns, but statistically, if you look at funds in China, you look at funds in the U.S., you look at funds in Europe, that all holds true. So, we’ve seen our loss ratios come down to a level that they’re lower than the buyout industry on one hand. And the other hand getting back to the old adage that you lose a lot of stuff, you do lose the companies. You just don’t lose as much money.

Matt: So, David you’ve been great partners with us at Madrona now for almost 15 years. And you know, that was back when the cloud was just getting off the ground with AWS and then later Azure, which of course are both based here in Seattle. I’m curious what got you and Top Tier excited about the Pacific Northwest as a region for venture capital as well as ultimately Madrona.

David: It’s a great question. Two things, first of all, more and more of our portfolio companies, which early on was predominantly Silicon Valley-based firms, were coming out of the Northwest. It became evident to us that there were essentially good things happening up north. And then we also had this strong belief that the cloud market in particular was going to be a big part of technology going forward. So, we wanted to sort of double down on that by getting more exposure to essentially ground zero for cloud, which is Seattle, in our opinion.

Matt: Well, we agree with you.

David: Yeah – you agree, but I mean, in general, that wasn’t obvious 15 years ago, but that was really the motivation. Seattle’s been kind of an interesting market for technology at a high level because the employment base has been for so long sucked up into a handful of really large companies. There used to be kind of the adage that if you really wanted to build a special business, you went to the big city. And then what was happening — the two things, one thing was the cloud activity that we wanted incremental exposure to if you will. But the other was that we started to see, finally, that the entrepreneurial ecosystem being generated by those large technology companies was really starting to be self-generating. And then what happens usually if you look at all the different regional markets and whatnot in the U.S. or different places around the world, you end up with this sort of flywheel of entrepreneur and startup sort of muscle memory, if you will, that allows both the entrepreneurs to invest in the businesses, but the businesses essentially generate employee capital, employee growth that you can then build upon to build an ecosystem. And so, what’s truly happened in the last 15 years in the Pacific Northwest in particular in Seattle specifically is that you’ve now that market is comparable to any other regional market in the U.S.

It doesn’t attract as much capital, a la the statistics because you don’t have as many firms up there, but I can tell you that the people that are up there think that the investment opportunities are just as good as San Francisco.

Matt: Well, we’re going try to keep spinning that flywheel.

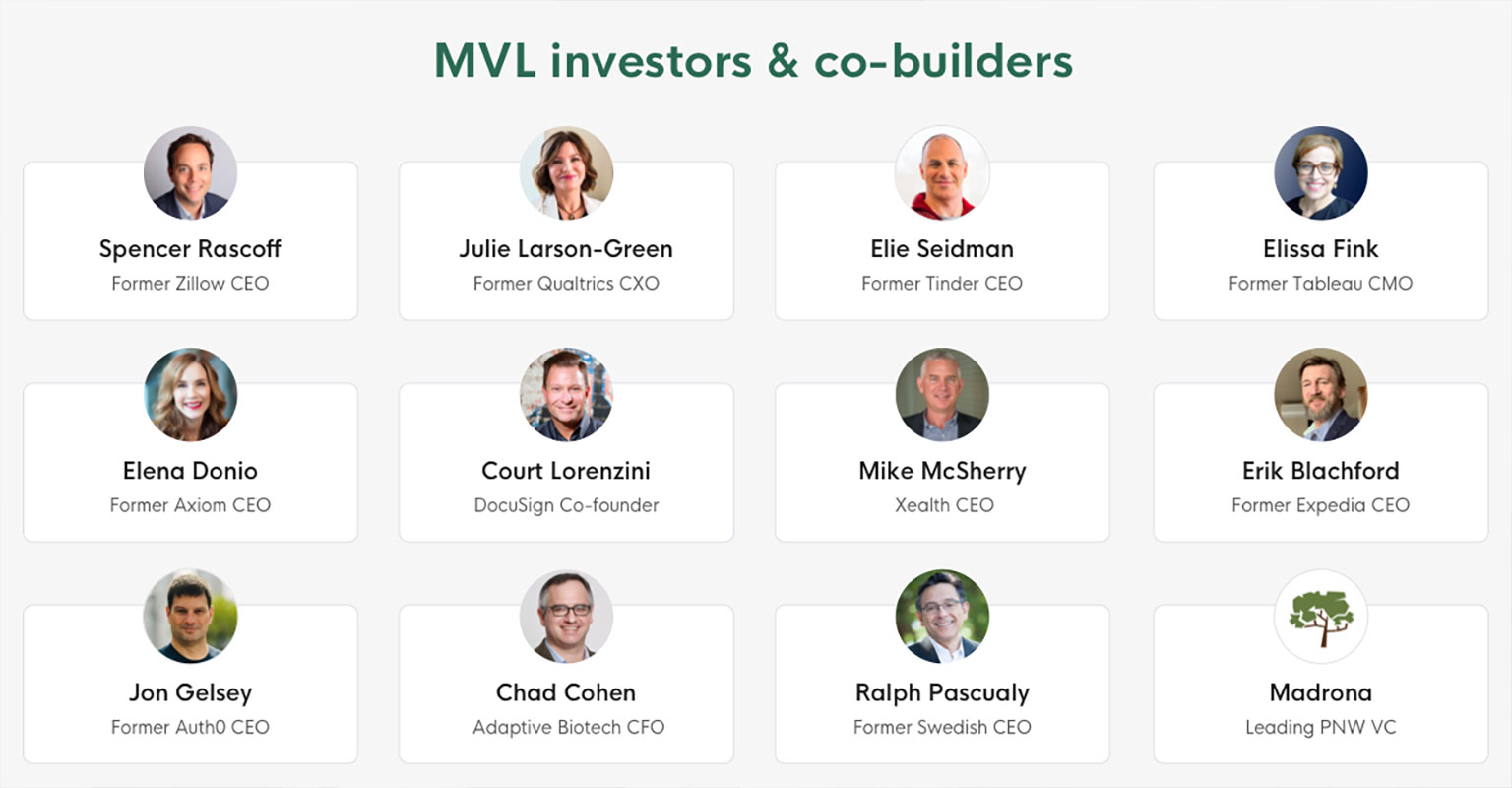

David: Yeah. Well, you guys have done a great job. We spent a bunch of time and really felt very, very confident about where you and Tom and the rest of the partnership were headed at the time, as well as the relationships you had in the community in a way that we thought we’d get a disproportionate view of high-quality deal flow, as it relates to what you were going to look at and then ultimately made its way into our portfolios. And so that was the reason for originally investing. But the other thing that happened is we had an opportunity both to co-invest with you, which we’ve done in a number of companies, including Smartsheet, but then one of our local foundations down here decided to do some secondary sales and that gave us another opportunity to partner with Madrona and buying a portfolio of fund interests in your funds and to the point where now I think we have more exposure with you than anybody else, which is something we’re excited about. We’re big fans of the market. We think you’ve done a great job with the team and where you’re headed. And ironically, it’s probably four or five times better than when we started.

Matt: Well, thank you for all of that. And the feeling is very mutual on the partnership. And yes, you know, we don’t very often have situations where there’s a secondary in Madrona, but that circumstance where they change the CIO at that group. And the new CIO wanted to do some different things. And the great thing is that we were able to work with you all and ultimately own a piece of that ourselves. And so, I think everybody that was on the buy side of that trade was very, very happy in the end.

David: Yeah, it’s been a great transaction for everybody.

Matt: Certainly, the market conditions have changed a fair bit in the last set of months. You and I have talked about this before, and I’m curious as you kind of look down the road a little bit, we’ve got these different strategies — primary investing, secondary investments into funds, into companies directly. What’s your view on the macro just to start? And then we could talk a little bit about where you see more or less opportunity as a result of the macro environment.

David: Well, I’m selfishly optimistic. I think for the first time in probably 30 years, we have a rising rate environment. And I think the markets in general, especially the overpriced technology stocks, or the bigger momentum stories, are just being reset as to how you want to price growth when you have a rising rate environment. And we’re going through this natural churn as we reprice things. What I think, at the end of the day, you have to rely on ultimately is fundamentals. And the fundamentals of our underlying technology companies, especially the ones that have gone public recently, are still very, very strong. So, I think ultimately those prices that have been pretty radical, that declines have been pretty radical. I think they’ll get rationalized at some value that’s different than what we were at in March, for instance, but I don’t think, because the fundamentals are so strong that we’re going to stop pricing growth in those businesses. It’s just going to be at a different, multiple. And so, the market’s trying to figure out what’s a practical rationalization for growth and the value of growth.

Matt: And I think probably a lot of our listeners have seen the charts where the 5-year trend and 5-year average of SaaS companies, for example, was maybe in the eight times their forward 12 months revenue. And it went as high as like 17, 18 times even last fall. And now we’re below the 5-year average, you know, kind of in the six to seven times range and yet a lot of these companies are continuing to grow. I think there’s been one other factor. It’d be interesting to see if you’ve seen this as well, which is there was almost a growth at any cost. You’re now seeing a pretty hard swing back to cash flow break-even or better — control your destiny with positive cash flow as key criteria, at the expense of some growth people are okay with less growth, as long as you’re very close to, and you have a clear path to sustainable cash flow positive.

David: This is the notion of fundamentals. At the end of the day, growth at any cost ultimately gets outpriced in a way that you’re going to have to reset. It’s happened in the late nineties. It’s happened several times in the last two decades. You know, cash flow break-even is obviously the holy grail for these, especially the IPO companies that have gone out in the last two years. It was always the anticipation when the company went on the road that that would happen in a reasonable period of time. I think during COVID, because of the demand for technology and, frankly, those companies’ products, they kind of threw that aside and said, the world’s going to let me get by without having cash flow break even. So, bringing that back, I think, is very constructive. To me, it’s where things should net out anyway. So, I’m not against it. And I think, having a little bit of discipline in your management is not a bad thing. So, I think it’s okay.

Matt: You all you know, invest in primaries and secondaries all over the world. You also have, if I understand it correctly, a pretty geographically spread out investor base of groups that invest into Top Tier. What are you seeing globally if we zoom out from the United States in terms of capital interest availability and how folks are thinking about these changing market conditions.

David: So globally investors started allocating pretty regularly to venture capital, really starting about six or seven years ago. In the last five years, it’s now really cemented as part of a portfolio allocation strategy. If you talk to consultants like Cambridge, or you talk to the endowments or you talk to even the big pension funds. And then ironically the benchmarking that all those places use has a mixture of assets that typically has venture in it. And because venture has performed so well, especially in the last five years, it’s outperformed every equity class there is. People are having their benchmarks start to beat them in a way that they’re starting to keep that allocation and worry about catching up. So, we don’t see any real materials slowdown in venture portfolio allocations. We do see pacing, as it relates to deployment into the asset class, ebbing and flowing really with what is happening at the balance sheet level of the investor. So, think about — I have a blended portfolio of listed stocks or fixed income or whatnot. If those things go up or down then it improves your balance sheet if venture goes up and down, it improves your balance sheet. But all of them have a certain weighting that the CIO typically wants that mix to be, and if they get out of line, then that might slow down or accelerate pacing just depending on where you are.

Matt: Let’s say I’m trying to have 25% of my investments be in private equity and venture, and they’re all still basically at the same values. But my public stocks have gone way down, just mathematically, my private company holdings are going to be higher as a percentage, and I might be out of whack in terms of my percentage allocations that I’m looking to achieve as a pension fund or an endowment or a foundation. Then there’s a whole bunch of things, including this kind of, I guess, leads a little bit into why it might be a good cycle here in the not-too-distant future for the secondary markets again.

David: Yeah, we’re very selfishly bullish about that opportunity. What we do is eat and breathe venture capital and technology, but we’re very excited about the cycle in front of us. And then what we see is especially some of the more aggressive investors, where we think they will have that what you were describing, we call the denominator problem, where the denominator is shrinking, but their exposure to private assets hasn’t really changed. Over time, what happens is they typically are selling off exposure, and we think there’s going to be a lot of very interesting opportunities for that probably after the second quarter. And that’s because of the way the markets have responded and, frankly, the way the private markets respond to corrections. It usually takes two or three quarters for valuations to change. But in the meantime, the public markets have corrected overnight, and so you end up with this disproportionate overweighting in private assets in a way that I think will have investors starting to think about rebalancing later this year and potentially into next year. And so, we’re very enthusiastic about what we see coming.

Matt: There’s also an additional timing element there because so many of these nonprofits, a lot of them are educational endowments, and their fiscal year ends at the end of June. And so, they have their kind of get their final year-end numbers. They have to face the board

David: And the auditor.

Matt: And the auditor.

David: And the auditor is going to make them stay true to their charter. And we expect that market, in particular, to be rebalancing quite a bit in the second half of this year.

Matt: You talked a little bit about the thesis on cloud and that one has been a very strong one. And in Seattle, I think with Amazon, AWS and Microsoft Azure, and even a fairly substantial presence for the Google cloud teams up here has really, you know, is for all kinds of reasons, I suppose, the cloud capital of the world. But what other big themes or thesis, you know, either, in the U.S. or abroad are really on your radar screen today.

David: We think there’s been a total sea change with COVID around the use and acceptance of technology across some very major gross domestic product slices. So, health care is one of them, drug discovery has gotten better and better, but the use of technology in the hospital systems and the medical community, and I don’t know how many people went to the doctor’s office during COVID, but we certainly had Zoom calls with doctors. We just think that whole ecosystem is ripe for innovation and change. Education is another space — all the kids learned how to go to school on their computers. And ultimately, I think that whole space is going to be ripe for change. Transportation, logistics, the whole notion of the fact that you didn’t have to own a car or, frankly, you didn’t have to go to the store because stuff was facilitated for you. I think it’s becoming commonplace in a way that that whole part of our gross domestic product is going to be materially impacted. And we don’t as an economy really understand that yet, but I do think it’s going to change things like insurance, how we ship things and a bunch of other stuff. And so, that’s another slice of the GDP that’s going to change. And then technology continues to always kind of cannibalize itself, but machine learning and artificial intelligence, which are a big part of your effort there, and especially your work with some of the institutions up there in the Seattle area, that’s becoming a more and more commonplace component of software in a way that you can see that there are these big companies like Google and Microsoft, and Salesforce that have a lot of startups that are very interested in innovating or out producing by using machine learning and artificial intelligence. I just feel that’s going to be more and more standard in a way that we’re going to again have another kind of full rotation in the tech stack.

Matt: Well, as you know, I think we had dinner maybe five years ago when this was when we were still quite early in the era of applied machine learning, or we like to call intelligent applications. And I think this is one of the neat elements of Top Tier is you all were curious, too, and wanted to have a deeper discussion. And we got a group of friends together and dug into that topic. And now we’re seeing just a lot of affirmation, whether it’s in industries like insurance that you mentioned or healthcare and increasingly life sciences, it’s going to be very, very transformative in the years ahead. I think I’ve heard you say, ” Technology is business for the future.” When you kind of go around the world, you talk to the folks investing in your fund do they see that too? Are they more and more buying into that as a core thesis of what they need to have in their portfolios?

David: Well, let’s spend a minute on global investors. Yeah. I talked earlier about venture allocations, kind of being a fixed part of portfolios — that allocation typically sits in the equity component of portfolios, as it relates to sort of where the piece is and the balance sheet. Most of the pension assets in the world are really yield-oriented, and that’s primarily because they’re trying to generate 6 to 8% returns to meet their actuary and fixed income could do that for them historically. Today that hasn’t been the case, and so they’ve slowly started to add more equity-like things such as real estate or private equity or venture capital. In markets where you had culturally the ability to buy something and see it go up in value like you do in the U.S., that’s been a very large growing component of portfolios. It’s gone on average from 2 to 3% of a portfolio — venture capital has — to now it’s probably approaching 5, and that’s those are material moves in those programs. In the family office world, it’s now running in the 20 to 30% range. If you go to places like Europe, where fixed income is such a big component of the investor base, it’s slowly getting there. So, some of our larger investors are in Europe, and their blended equity portfolio is now 50% of what they do, and their private equity is now 15, including venture capital. Ten years ago, that number was more like 30, sometimes 20, as far as equity is concerned. And then venture then was a subset of that. So, we’ve seen that growth, but it’s been slower, more measured and more risk adverse. Asia still relies heavily on their fixed income markets. You know, if you think about their traditional pension markets, like Japan is the second-largest pension market in the world and they all follow the large sovereign pension funds there, and those are 80, 90% for the most part Japanese bonds. They’re large pools of capital, they’re trillion-dollar pools, but the ratios kind of dictate the trend and then if they want to do private equity, they struggle to do venture capital, because they worry about losing money. When investing, I’ve started to think about risk and where it lies and sometimes there’s risk of missing the upside. And I do think most of the Asian pension funds have missed a lot of upsides.

Matt: I tend to agree with you there. I mean, there’s some exceptions, of course. And you know, I think the folks in Singapore have done a particularly good job of diversifying into some of these different areas.

David: The sovereign wealth funds have done a better job thinking about equity than the pension systems in those communities. Yeah.

Matt: So, to bring this back to the entrepreneur for a second? What are the implications to them? My macro takeaway is that there is a growing amount of capital from pension funds and wealth assets and then you get the foundations endowments that have done very well. This seems to be generally something favorable to the entrepreneurs and the companies because there’s more capital that’s looking to find its way into private companies. Is that fair to say from your end or do you see it differently?

David: I think the capital will be abundant. But selection and actual fundamental application is still going to be the tricky bit. So that’ll take skill both on the entrepreneur’s side, as well as on the manager’s side at firms like Madrona. What we see today is that there’s an abundance of seed capital, right? So, you can get a company started, but really knowing how to build a business and get it to become successful is a whole other problem. There’s an abundance of series A through D but picking to make that stuff work is still the really, really differentiated activity. You know, most people have networks, and most people have what I would call service activities, but being able to see around corners and pick the right stuff is the hardest bit as it relates to traditional venture capital. In the growth market where a lot of the valuations are driven off of public equity activity. The people that were doing that, a fair amount of them had public equity investment funds, like mutual funds and hedge funds, and things of that nature. I think that stuff will ebb and flow with the public market valuations and the capital there will also ebb and flow a little bit with public market valuations because they too have denominator problems in those portfolios as public stocks come down.

So, we expect that market to slow down. We expect valuations to come in at the early stage and seed stage level valuations, they accreted but I think for the right reason, which was the fundamentals were in a pretty good spot for most of these seed companies. They had some sort of product, so you weren’t really doing a really true raw startup like you were maybe 10 or 15 years ago. So, to me, this is the time where the guys that roll up their sleeves and really do the good work actually are going to be the winners, whether it be an entrepreneur or an investor.

Matt: Well, I think this has been a really helpful conversation. You know, a lot of times the entrepreneurs we work with are very curious about how we get our capital and some of these other mechanisms — the primary and the secondary markets. I really want to thank you for taking the time to walk folks through some of that history. Some of the things that have changed, some of the things that are going on now and how these different parts of the kind of capital world exist and function. So, thanks very much, David, really appreciate it.

David: Matt as always. It’s a pleasure seeing you and a pleasure to spend time.

Coral: Thanks for joining us for this week’s episode of Founded and Funded. If you’re interested in learning more about Top Tier, please visit TTCP.com. Thanks again for joining us and tune in, in a couple of weeks for our next episode of Founded and Funded.